None Shall Sleep

How the Belt and Road Initiative built a foundation that scammed billions of dollars from Americans

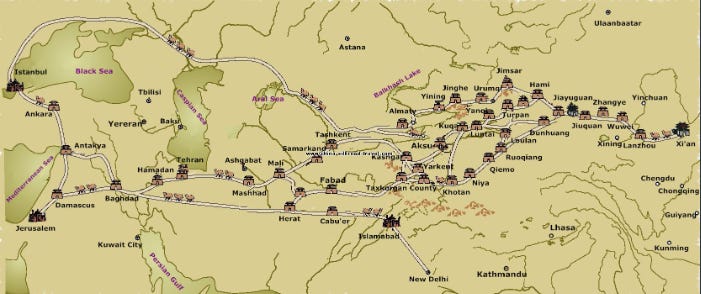

In September 2013, President Xi Jinping stood beneath Kazakhstan’s pale blue sky and unveiled his vision for a New Silk Road. He spoke of ports and pipelines, of prosperity and peace - draping his speech in 2,000 years of Chinese imperial history.

That project became the Belt and Road Initiative.

Beneath the slogan and flags, a criminal element saw opportunity - and used the Belt and Road as a cover for their schemes. Triads, businessmen, and ranking members of the CCP worked together to build out scam compounds across Southeast Asia that have defrauded tens of billions of dollars from Americans

I’ve combed through hundreds of sources, traced the money and names - from Beijing to Hong Kong to Burma - through company filings, Chinese language social media, and buried websites to uncover who was behind these scam operations.

The work that western journalists simply won’t do.

This is the story of how China’s grand dream for global trade and power laid the foundation for one of the world’s largest organized criminal enterprises - in an essay that I call:

None Shall Sleep: Inside the Belt and Road Empire of Fraud

Note: If you’re reading this story and you haven’t subscribed to this newsletter, please do below. I’m working on several long form essays like this one, that explore the underbelly of our world, narrated from my own personal experience.

Don’t miss the next one.

Subscribe today:

Final Note: If you’re reading this on email, click this link to go to the full post on the Substack website.

The Chemical Frontier

It was a brisk 10 degrees centigrade on the morning of February 9th, 2020, in Kutkai, Shan State, Burma (yes, I will call the country Burma throughout - deal with it) when a joint operation task force composed of regional law enforcement - termed Operation Golden Triangle 1511 - raided a dusty and sprawling narcotics production facility.

The rusty corrugated roof-topped warehouses, dozens of blue polypropylene plastic drums, and hundreds of woven rice sacks concealed a massive amount of drugs. After it was all tallied, the three month long operation seized over 18 tons of meth, a ton of opium, another ton of ephedrine, 300 kilos of heroin, and 3,748 liters of methyl fentanyl - on top of another 41 tons of precursors and 160 tons of pre-precursor chemicals that were to become fentanyl.

It was a historic drug bust, Asia’s largest.

The majority of the meth was destined for the broader Asian and Oceanic markets: Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, where it could fetch 100-500 times what it cost to produce.

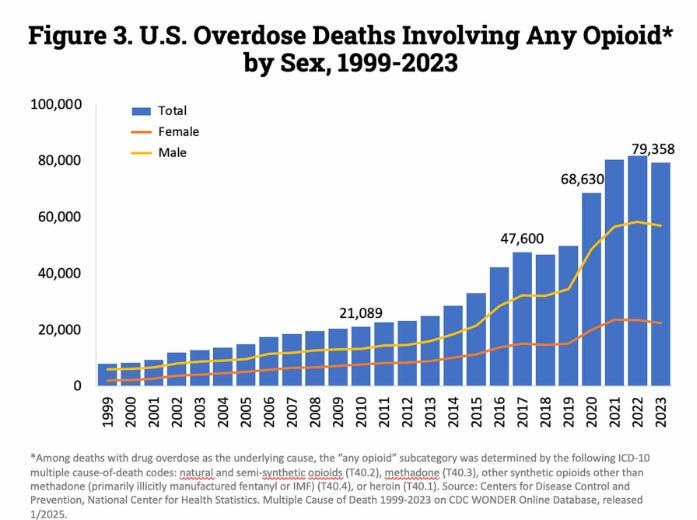

But the fentanyl was to be shipped further ashore. The vast majority of it would end up in the United States, which had been suffering from an epidemic of opioid overdoses that was about to accelerate to new heights that year.

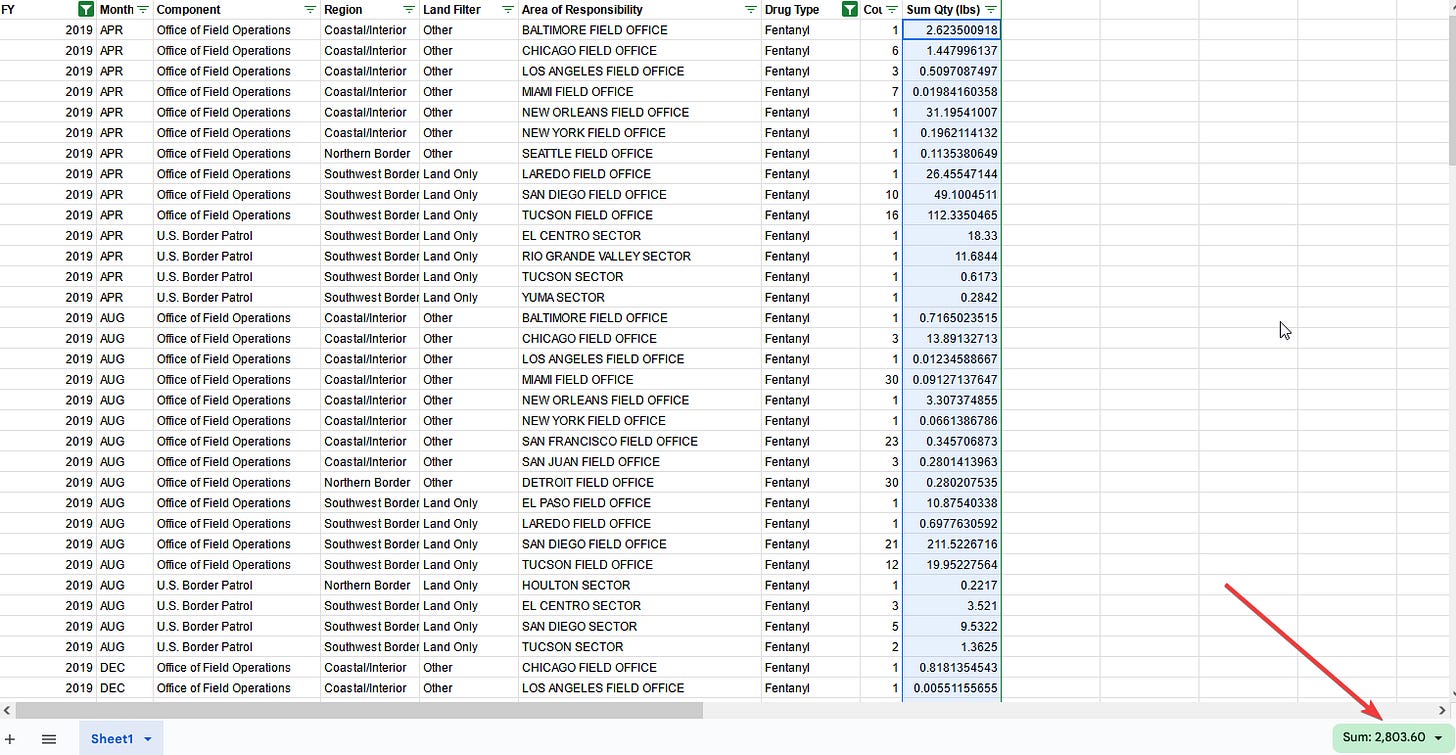

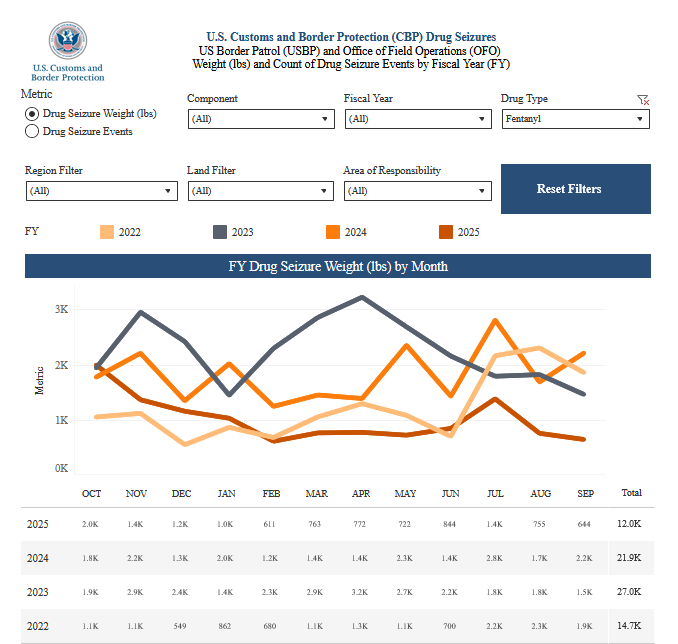

The amount of fentanyl coming into the United States during this time is hard to determine, but we do know how much was seized. The US Customs and Border Patrol website maintains a fairly robust data set that breaks down the figures by date, narcotic type, field office, and weight. In 2019, there was a recorded 2,803 pounds of fentanyl seized. This was up from a paltry sum of 70 pounds taken in 2015.

A few years later, by 2022, that number inflated to over 14,700 pounds and then nearly doubled again in 2023 to 27,000 pounds of fentanyl seized by US Customs and Border Protection.

It’s important to underline the fact that seizures are a small slice of the pie, in terms of the total amount of narcotics entering the country. It’s fair to estimate that seizures represent only 2-10% of that volume.

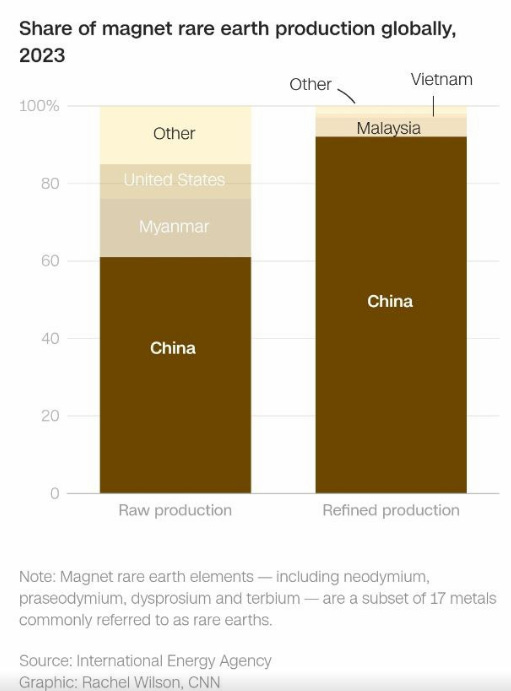

The common story about fentanyl that goes around is that China is the main producer of the potent opioid. This is true, but it misses some nuance and interesting details.

After all, why was fentanyl being made in that dusty warehouse in the backwaters of northern Burma?

I’ve mapped out a timeline of events that will help answer that question. This will also help paint a picture of how Chinese criminality proliferates in other fields, like scamming.

A year and a half before the Burmese drug bust, on November 30th 2018, the world’s top leaders met in Buenos Aires for the 13th G20 Summit. At a dinner that evening, President Trump sat across the table from President Xi and pressured the Chinese leader to solve the supply side of the fentanyl problem.

Whatever was said between the two titans seemed to have worked, as not more than a day later, the White House Press Secretary issued a statement that read, “Very importantly, President Xi, in a wonderful humanitarian gesture, has agreed to designate Fentanyl as a Controlled Substance, meaning that people selling Fentanyl to the United States will be subject to China’s maximum penalty under the law.”

Prior to this handshake agreement, fentanyl production in China was illegal - and penalized harshly, with capital punishment - but enforced with whack-a-mole tactics. The production of synthetic opioids happened in a swampy gray area of Chinese law. New variants of fentanyl were constantly being churned out to avoid enforcement. Analogues with slight chemical tweaks would pop up after prior ones were identified and scheduled.

The approach to this problem changed in April 2019, a few months after the Trump-Xi meeting, when the Chinese government announced it would place all variants of fentanyl, as a class, on the list of controlled substances - as opposed to adding each synthetic variant to the scheduled list one by one. This was a serious blow to fentanyl production in China and dozens of factories were shuttered overnight.

But strangely enough, fentanyl shipments into the United States, along with the correlated rise of opioid overdose deaths, continued to rise. Those facts are difficult to reconcile - the deadly synthetic opioid was still being produced and at seemingly greater volume than before. And remember - not more than eight months after China followed through with their commitment to crack down on domestic fentanyl production, that dusty warehouse in northern Burma was discovered.

An interesting thing about fentanyl is that it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to produce the stuff - but it does require some degree of know-how to follow instructions close enough to make the right end-product. In the month that followed the drug bust in Burma, over a hundred people were detained and arrested in connection to the facility. Many of them were not Burmese nationals or members of the ethnic minorities in the region. They were Chinese and Taiwanese chemists who were brought in, as they could facilitate the production under the watch of the warlords who really rule there.

This is how the fentanyl kept flowing - a large share of production simply shifted away from mainland China and into Burma, a nation ruled by a patchwork of regional ethnic rebel groups and an entrenched military junta that fights for control on behalf of the central government. The country was a witch’s cauldron that was only two years away from boiling over into another phase of its civil war, one that had been ongoing for seven decades.

It’s a pattern that I’ve observed across multiple cases. While direct state orchestration is hard to prove, there is a consistent correlation between regulatory crackdown in China and the reemergence of criminality in third party nations like Burma, where the rule of law is absent. I can’t draw an unshakable direct line from the politburo in Beijing to Burma in the case of this narcotics bust, but it’s important to bring attention to this drug case for what follows in this essay.

Burma had only recently opened up to the world, after the nation passed the Foreign Investment Law in 2012 - under the guidance of President Thein Sein, who also released the more internationally well-known Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest.

This legislation made it possible for companies involved in real estate, telecom, insurance, and mining to enter the country that had been hermetically sealed since 1962, when General Ne Win seized power in a military coup and established the “Burmese way to Socialism.”

Foreign investment trickled in at first, but accelerated over the following five years. China took particular interest in the country and Burma became a focal point for burgeoning Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects. Special Economic Zones, or SEZs, were mapped out across the Burmese landscape from the Mekong down to the Irrawaddy River, from the infamous Golden Triangle to neglected border towns like Myawaddy.

Aung San Suu Kyi visited Beijing in 2017, where she attended a forum on the BRI. What followed a year later? Burma officially joined the ambitious BRI plans in September 2018, after the two nations signed a 15-point memorandum of understanding.

The plans to develop Burma with Chinese public and private investments were grouped under the acronym CMEC, or the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor. This was a symbolic gesture towards the historical relationship between the two countries - an affinity that is called in Burmese as “pauk-phaw.”

Projects included in the 1,000 mile stretch of development were new road networks, railroads, and shipping lanes to link China to Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Russia. The Kyaukphyu SEZ, in western Burma, would give China strategic access to the Indian Ocean. Developments on the border between Shan State Burma and China’s southwestern and landlocked Yunnan province were also detailed, as these would unlock new trade routes for Chinese goods to flow out to the world.

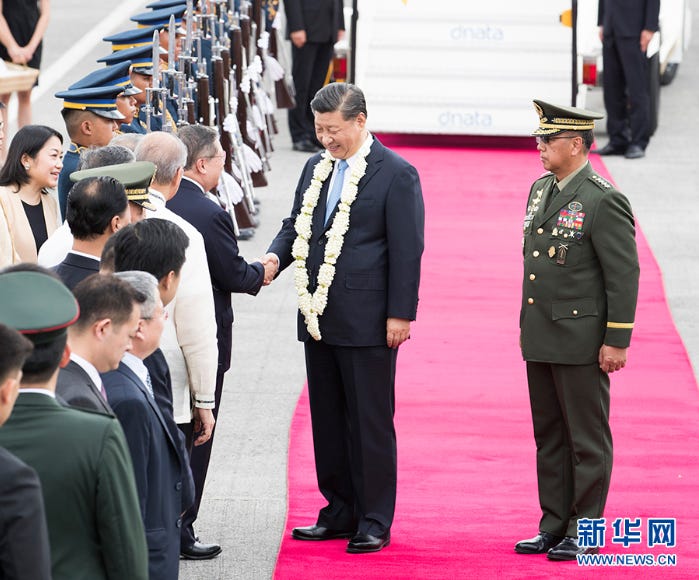

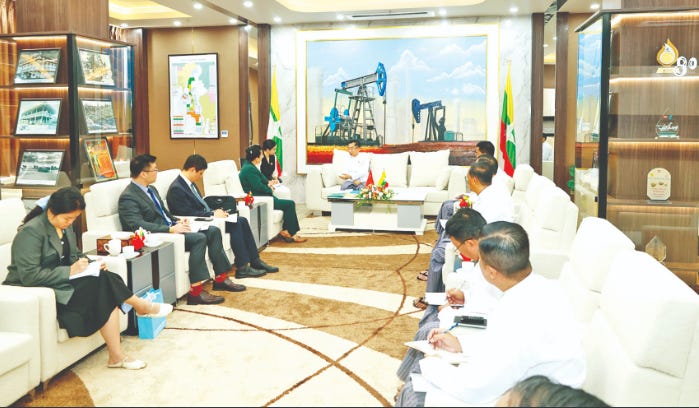

In April 2019, Myanmar and China signed another memorandum of understanding at the second BRI forum in Beijing that brought together 38 heads of state, over 6,000 representatives from more than 150 countries, and 90 international organizations. Again, Aung San Suu Kyi was in attendance - you can see her in the photo above at 9 o’clock.

This new agreement between Burma and China committed both nations to CMEC cooperation from 2019 to 2030. Remember, this was only a few months after the dinner meeting between Trump and Xi in Argentina where China’s president agreed to squash fentanyl, and it happened to be the same exact month that China announced the reformed laws around synthetic opioids to combat their production in the mainland.

There’s no direct, causal link between the PRC and that big drug bust in Burma that I introduced at the start of this essay. It’s easier, and frankly more logical, to make the assumption that criminal elements in Chinese society fled the strict measures that the government was taking against synthetic opioid production and brought their chemical factories to the lawless frontier of Burma.

But with all things in the Orient, as I’ll argue and demonstrate in this essay, the lines between what is sanctioned and illegal, what is public and private, what is known and unknown, are often blurred and difficult to suss out into something of a coherent, logical narrative by outsiders.

The western press has largely failed at identifying the key relationships, organizations, and social structures in China and the region that built the narcotics facility that was busted in early 2020 - just as it has fallen short in constructing a narrative that is able to account for the industrial-scale scam cities in Burma and Cambodia that have entered the news cycle this past month.

What happened with fentanyl in Shan State Burma wasn’t an anomaly. The same criminal networks that relocated their labs had simultaneously built up an infrastructure of digital scam compounds across Southeast Asia.

As opposed to the fentanyl factories and the circumstantial evidence about how high up involvement went with those, I am able to draw out solid, conclusive proof that the People’s Republic of China, their government, public-private partnerships, corporations, trade guilds, and criminal elements all worked together to build the Southeast Asian fraud centers that stole $10 billion from Americans in 2024 alone.

I’m also able to prove that the Belt and Road Initiative, one of President Xi’s pet policy projects, provided a backbone to the fraud by lending institutional and social capital.

I know who met together and when and where as the foundations of these scam cities were being laid. And just like how regulatory measures stopped industrial scale fentanyl production in mainland China only for it to pop up in neighboring Burma, so did the same thing happen with online casinos and other “digital entertainment” operations that served as a cover for straight up scam factories - China cracked down on internet gambling domestically, only for it to proliferate across the region in Cambodia, Laos, and Burma, right alongside the Belt and Road projects.

High-level criminals were given support from ranking members of the CCP, industry guilds, and political and business leaders from around the region - effectively green lighting the development of these scam centers in Cambodia and Burma.

The same gangsters who were behind the narcotic production that I opened this essay with can also be tied to the industrial-scale fraud cities. I’ve been able to chart out the who, when, and how they were built, along with other operational details that haven’t been covered in the anglophone press.

Crypto currency companies operating out of Singapore and Macau entered to provide a convenient method to launder funds in and out of the scam cities. I’ve found what companies these were, the names of their founders, and how much money they brought in.

And finally, I’ll tease out a common thread that runs through this all - one that has been absolutely ignored by western journalists - of a group that is almost 400 years old, with mythic origins and over 300,000 members worldwide: the Hongmen or Vast Family (洪門), known also as the Tiandihui or the Heaven and Earth Society (天地會) - or put simply, the Triads.

First, let’s explore the origin of the Belt and Road Initiative, what it looks like from the inside, its relationship to Special Economic Zones, so that the fraud centers in Burma and Cambodia, which have stolen tens of billions of dollars from Americans, can be properly understood.

It’s time to construct an objective, clean, and thorough narrative on the matter - as journalists have failed to do so far.

First Stop on the New Silk Road

The Rosetta Stone for understanding the Belt and Road Initiative can be found in a speech that President Xi Jinping gave at Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev University on September 7th, 2013. This was the first time that President Xi publicly proposed a Silk Road Economic Belt, which would encourage innovation and cooperation in regional Central Asian countries.

President Xi wasn’t just making a speech in Kazakhstan, he was consecrating the 21st century Han empire.

To underline this point, his speech tapped into ancient Chinese history, specifically the Western Han Dynasty that reigned between 206BC to 24AD. In that time, an imperial envoy and explorer named Zhang Qian traveled through Central Asia, western China, Greco-Bactria, the Indo-Greek kingdom of Shendu, along with the Parthian and Seleucid Empires of Persia and Mesopotamia. His travels were well documented by Sima Qian, a historian who can be compared to Herodotus and Thucydides in the classical world.

The travels of Zhang Qian were legendary, especially for the time, and offer a unique and often overlooked insight into the 2nd-century BC Orient from someone who was on the ground. President Xi rhetorically invoked Zhang Qian because he was dispatched by the imperial Han court to explore the western lands beyond the Middle Kingdom’s borders - and he returned with reports for the Emperor that detailed civilizations, some barbaric and others sophisticated, that could become new trading partners.

These diverse empires in the West produced strange and attractive goods and in turn they admired what the Han brought from the East.

The efforts of Zhang Qian paid off, as trade missions soon followed his explorations, and the Silk Road as we know it properly started.

President Xi referenced Kazakhstan as being a major waypoint along the ancient Silk Road, and exalted the contributions and cooperation that the people there gave to the Chinese. He underlined the history of friendship through the ages - more than two millennia of interaction with people of different races, beliefs, and cultures, who found mutual benefit through trust, tolerance, and learning.

In order to capture the ideals of the old Silk Road and make them useful for the modern world, five pillars were identified by President Xi in his speech: policy coordination; infrastructure connectivity; trade facilitation; financial integration; and cultural exchange.

It’s a system of influence where Beijing no longer needs to coordinate every detail.

On paper, it reads like an idealistic manifesto. In practice, it functions as a blueprint for influence. Scratch the surface, and the sentimental shine cracks - and the details on the ground reveal a reality that puts Beijing and China’s interests front and center.

Policy coordination by aligning national and economic development through multilateral dialog becomes a way for Beijing to find leverage in the internal planning of partner nations. This is what happened in Burma, Cambodia, and Laos, along with several African nations, although the latter is beyond the scope of this essay.

New roads, railways, telecom, and pipelines that President Xi said would link the Pacific to the Baltic have emerged and alongside this connectivity so has illicit flows of narcotics, wildlife and human trafficking, and financial fraud centers - the focus of this essay - by opening corridors into nations like Burma and Cambodia with weak governance and rule of law.

Trade facilitation and financial integration become Special Economic Zones and crypto and Yuan-based laundering systems that can seamlessly plug into the Belt and Road infrastructure to obscure it from the heavily regulated western banking system’s oversight. In this essay, we’ll zero in on the Shwe Kokko Special Economic Zone, how it was created and funded, who was behind it, and why it became a hub for scamming billions of dollars from Americans.

And finally, cultural exchange is a diplomatic way to position Sino-oriented guilds like the China Federation of Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs and quasi-underground criminal organizations like the Hongmen society, a Triad group, as the primary method to deploy and develop these projects. It doesn’t have to be Beijing that gives the nod to any particular Belt and Road project, and President Xi doesn’t need to be there to cut every ribbon. There already exists a robust domestic and international network of Chinese who will do the work for them.

What was announced in President Xi’s September 2013 speech in Kazakhstan morphed over the years into what is now called the Belt and Road Initiative, or One Belt One Road in Chinese (一带一路), formalized in 2015.

This happened in stages.

In October 2013, President Xi proposed a China-ASEAN community and offered guidance on a “21st Century Maritime Silk Road.”

The following month, November 2013, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China called for speeding up infrastructure links with neighboring countries.

In early 2014, Xi looked to the Arab world to deepen ties there, and in the last months of that year he allocated $40 billion USD to a Silk Road Fund for these projects.

By 2023, China had spent over $1 trillion on Belt and Road projects and that number was expected to reach $8 trillion over the lifetime of the policy.

That doesn’t account for private investment into Belt and Road.

One of those projects, the Shwe Kokko Special Economic Zone, also known as the Yatai Water Valley Special Economic Zone, was announced in January 2017. Hundreds of millions of dollars of capital flooded in to build up a fraud empire from the swampy rice paddies on Burma’s eastern border. The man behind it, She Zhijiang, courted investors from the highest echelons of Chinese businesses, trade groups, and political elite.

She Zhijiang is sitting in a Bangkok prison today - although he’ll soon face extradition to China - as he was arrested by Thai police in 2022. The charges brought against him were based on his involvement with defrauding thousands of Chinese citizens - and his company, the Yatai Group, along with its compounds in Burma are still working around the clock to scam billions of dollars from Americans today.

The details of how the Yatai Group and She Zhijiang were able to pull this off are laid out step-by-step in the sections below.

First, let’s take a big step back so that we don’t lose the forest for the trees.

I’ll lay out what was happening in Burma that tilled a fertile ground for the Yatai Group’s scam compounds to take root and flourish.

Spoils of War and Crime

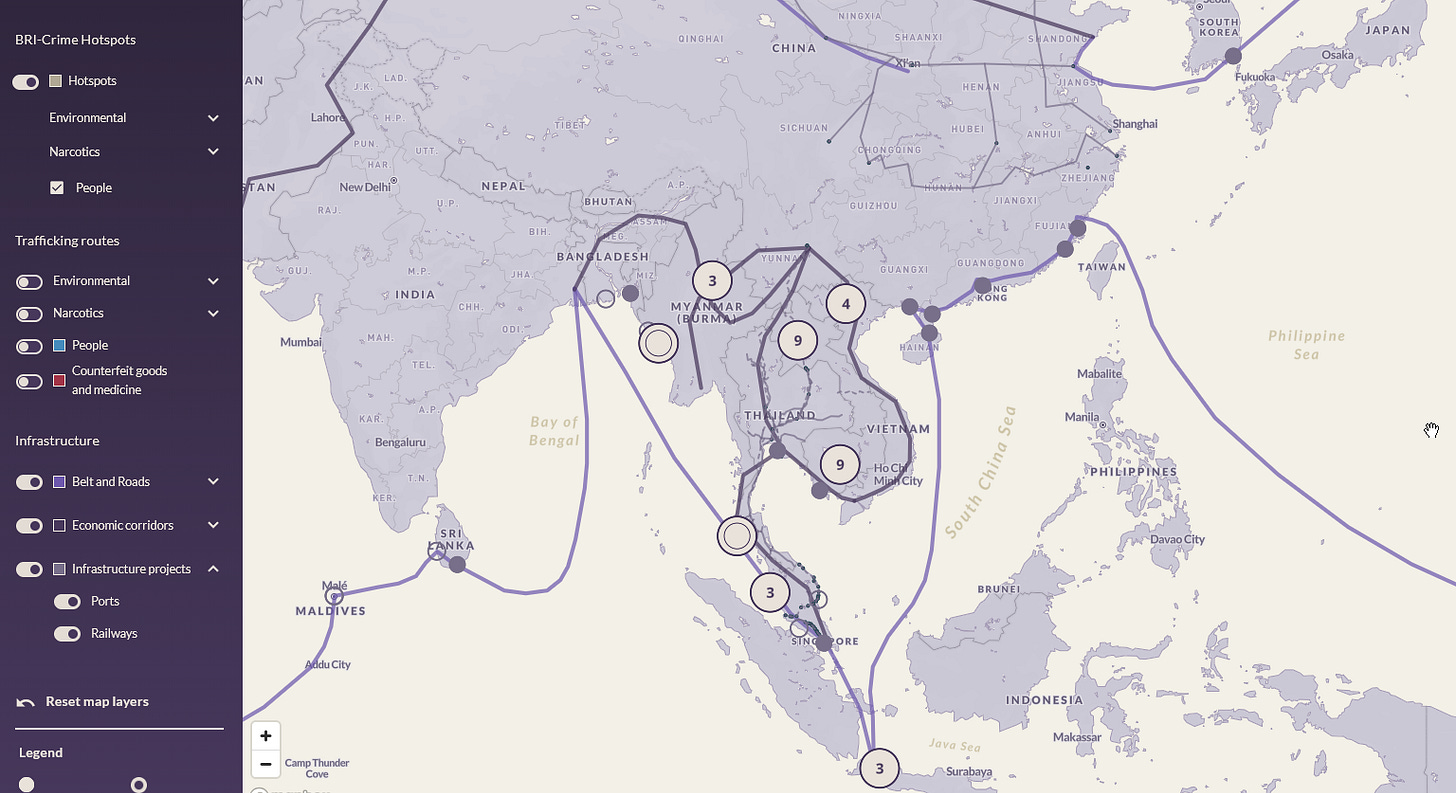

Sometimes it’s easier to visualize information - and throughout this essay, I’ll provide photos and maps that help illustrate the foreign lands, people, and crimes that I cover.

In this map, from the Global Initiative, the overlap between crime hot spots, Belt and Road projects, and other infrastructure can be seen. This isn’t comprehensive by any means, but it gives you a good idea about how policy experts are looking at this issue.

You’ll notice that Burma, Cambodia, and Laos are all central to Asia’s criminal underbelly - and sometimes, that overlaps with projects under the Belt and Road.

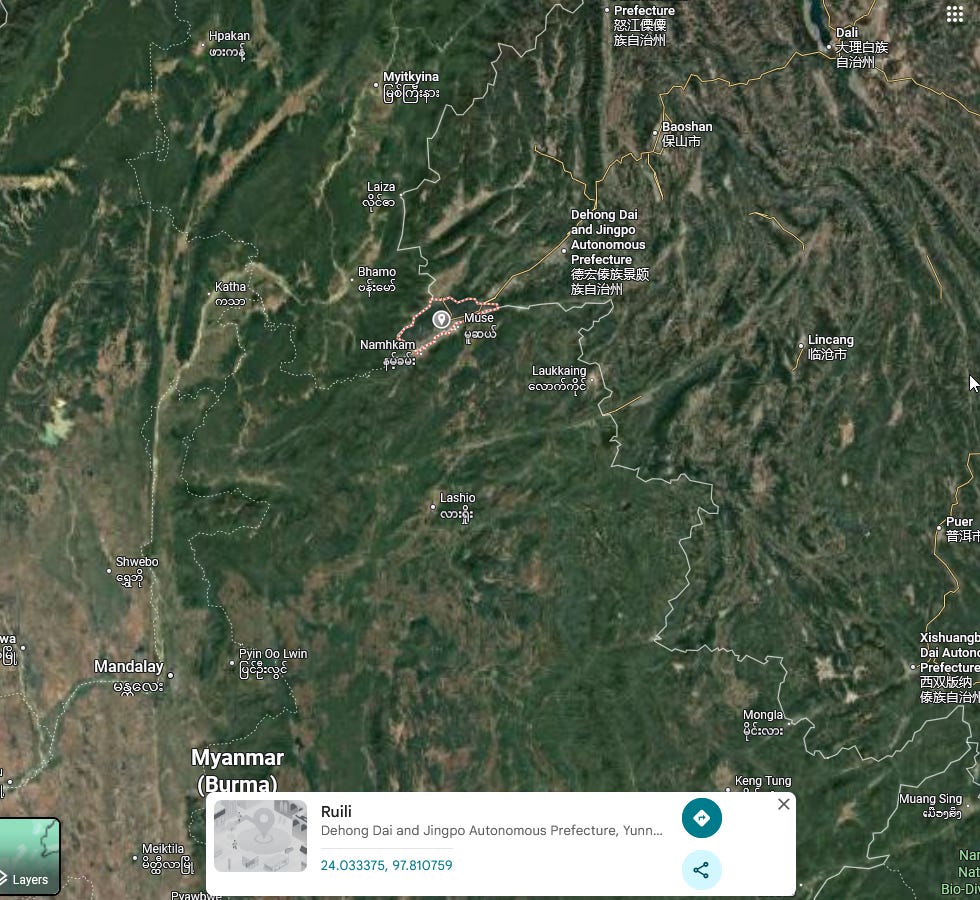

Here’s another map that will orient you to where I will take you in this essay.

Bringing our attention back to Burma.

In 2013, China stepped in to mediate early peace talks between the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) and the Burmese government. The summit was held in Ruili - that mid-sized border town, with the dotted red border in the map above, of about 250,000 that sits in a crook where Yunnan and Burma meet.

The geography throughout Southeast Asia that President Xi extolled as a “corridor of friendship” had become a corridor of crime - and nowhere is this clearer than in Burma.

A splinter group from the KIA, known as the Kachin Defense Army (KDA) based in northern Shan State, were conspicuously absent from the peace talks. In 2017, China stepped in a second time, offering their diplomatic strength to broker peace between the central Burmese government and a variety of ethnic factions - including the KIA and KDA.

After this meeting, President Xi wrote that, “China supports the efforts of the Burma government to promote peace and reconciliation, and supports Burma in safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests and national dignity in the international arena. Burma, for its part, has given China staunch support on issues involving China’s core interests and major concerns.”

Three years after this lofty statement calling for peace - and exercising the “policy coordination” pillar of the Belt and Road - that narcotics facility, mentioned in the beginning of this essay, was discovered in northern Shan State. And over the months following that bust, the Burmese military raided the KDA headquarters in Lwekham and found another stash of drugs that connected them to the larger narcotics facility.

The KDA was also implicated in offering protection to the narcotics facility and was in turn being paid handsomely for it, bringing in tens of millions of dollars for their services. This money was funneled into their war chest and bought them munitions and supplies. But they’re not the only ones involved in the narcotics trade in Burma.

When you start to comb through reports from the region and if your notes are thorough enough, every rebel group - they all have acronyms, btw - is profiting from the drug business in Burma. It’s an old tradition, too - going back to Khun Sa in the 1970s, the “greatest enemy the world has” according to the American ambassador to Thailand at the time. He’ll be a story for another day.

There are no clean hands in the country.

There’s also no evidence linking President Xi personally to narcotics production in Burma - that would be a stretch in any universe - yet the policies his government champions have created the permissive architecture where it thrives.

China’s diplomatic policy of supporting every side in the Burmese civil war tacitly facilitates the drug trade by providing arms, funds, and infrastructure to the groups known to be involved in making and smuggling narcotics. This same pattern can be seen in the scam industry that has taken root in Burma over the past seven years.

This is the Belt and Road’s true innovation - developing an ecosystem where the state doesn’t need to act, because its proxies, patriots, and profiteers do so on its behalf.

Case in point - in February 2017, a Hong Kong-based company called the Yatai International Holdings Group registered a subsidiary in Burma under the name Myanmar Yatai International Trading Co Ltd.

She Zhijiang founded the Yatai International Holdings Group in the early 2010s (important note, the Wiki for Jilin Yatai Group, a different Chinese conglomerate, incorrectly claims that She Zhijiang was its founder).

As an aside, the more that you dig into the relationships and businesses involved in the region you’ll quickly notice a pattern of shell companies and business registrations that make it difficult to pin down the who, what, when, and where - but the details are important nonetheless, and I am thorough in combing them.

By mid-April 2017, laborers broke ground on a 2,000 acre complex along the Moei River that forms the border between eastern Burma and Thailand’s western Tak province. According to reports, the project had $15 billion in backing - a figure inflated for PR purposes, but was likely heavy nonetheless.

At this time, the Yatai Group reportedly had over 3,500 employees across offices in China, Hong Kong, Thailand, the Philippines, Cambodia, and Burma, along with $3 billion in assets, and had established itself as a player in Asia in the fields of cargo transportation, airport and urban construction, sewage and water treatment plants, real estate development, industrial materials, food processing, large-scale spas, entertainment, and technology research.

She Zhijiang found an ally on the ground in one Colonel Saw Chit Thu of the ethnic Karen rebel faction known as the Border Guard Forces (BGF). He’s pictured here and also in the previous photo as he looks over a drug seizure.

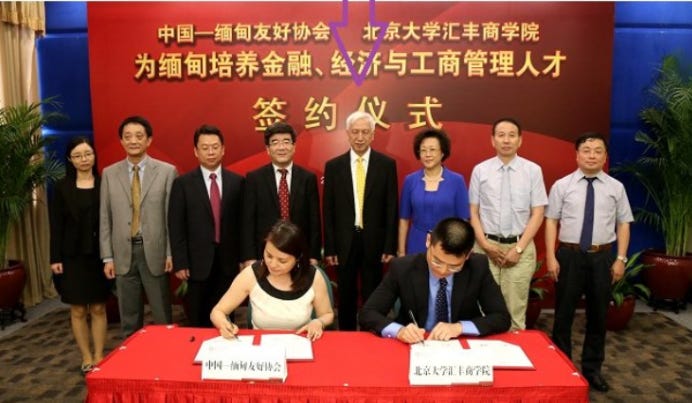

In September 2017, Colonel Thu and the Yatai Group signed a partnership agreement that was overseen by the China Federation of Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs (CFOCE) - a business guild with over 20,000 members, who we will return to shortly.

Plans for Shwe Kokko included hotels, shopping centers, KTVs, entertainment complexes, and an airport. By late 2019, significant progress had been made in building up the area, but the construction was seemingly never ending.

Dozens of multistory apartment blocks were built or under construction, each marked with red and yellow banners in Chinese. The four story De Yue Ju Xin Hotel offered rooms, but only at an hourly rate. Construction workers and Burmese staff lived in cramped, aluminum roofed housing. The main builder behind the projects was a subsidiary of the Chinese state-owned Minmetals Corporation.

Yet again, the lines between state and private enterprise, trade guilds, and third party political leaders - in this case, a war lord from the Karen ethnic group - blurred as the so-called Shwe Kokko Special Economic Zone took shape.

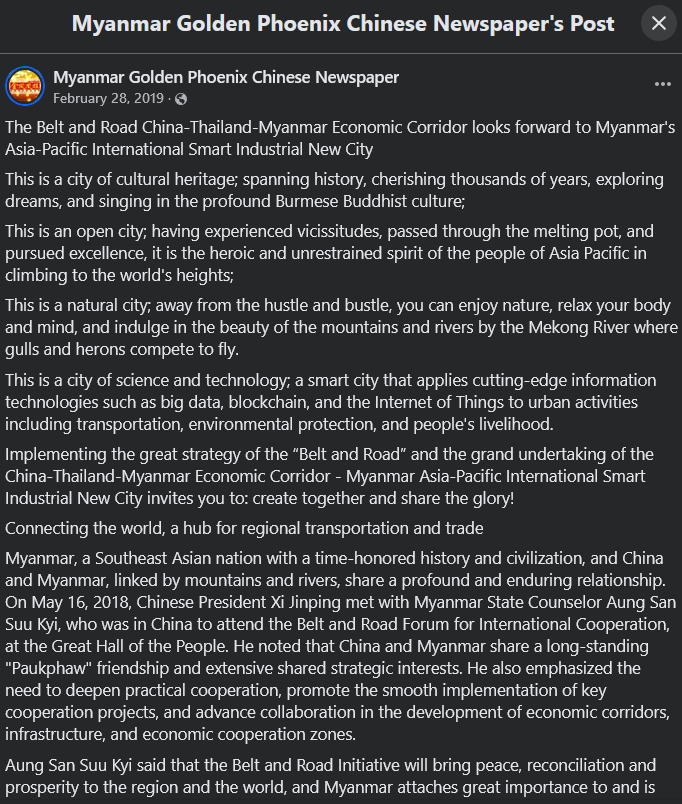

Press releases from the time, like the one that I grabbed from a February 2019 Chinese-language Burmese press outlet’s Facebook post seen below, proliferated across the internet.

These glowing articles weren’t limited to social media. One of the top financial institutions in Thailand, Bangkok Bank, published a report on their website that detailed meetings between the founder and chairman of the Yatai Group, She Zhijiang, and high-ranking Thai public officials such as the provincial governor of Tak province that bordered Shwe Kokko, the mayor of Mae Sot which is the border town on the Thai side, and other business stakeholders in Thailand.

This is to say that She Zhijiang was courting influence across the border and this became materially beneficial as it was later discovered that the scam compounds were being serviced by Thai telecom providers - although they did pull out due to pressure from Beijing in early 2025.

Economic development, a boost in tourism, and an increase in land prices were all cited as benefits that were soon to come through this partnership. The Bangkok Bank report also quotes Thai business and political leaders lamenting the missed opportunity Thailand had in not openly courting the Special Economic Zone arrangement like Burma had done.

But by the following year in 2018, Beijing caught wind of what was really happening at the far-flung Sino-outpost of Shwe Kokko - the newly built compounds were being used by criminal networks as offices for scam operations, which targeted victims across the world, from the US to China.

Locals started complaining about the lack of transparency around who was behind the construction and the influx of Chinese, who were increasingly engaged in illicit activity - the karaokes and casinos were the playground for the workers inside the compounds, where drugs and hookers were abundant, and people were starting to notice. Scams were afoot and a criminal element from China was moving in fast.

In June 2020, the Burmese government said it had formed a tribunal to investigate Shwe Kokko. But they weren’t able to visit due to COVID-19.

In order to save face, the Chinese embassy in Burma issued a statement two months later in August 2020:

“The Chinese and Myanmar governments attach great importance to related issues and have always maintained close communication and coordination. China expresses its support for this (referring to the Burmese government investigating Shwe Kokko).”

The embassy also underlined something in their statement that was later unconvincingly parroted in the western press: that the Shwe Kokko development was not part of any Beijing sanctioned Belt and Road project.

After the Chinese embassy in Yangon made their position known, the Yatai Group posted on their public WeChat account stating that, “This project (Shwe Kokko) is not the act of the Chinese government, but is still in service of the Belt and Road Initiative.”

Yatai Group went on to say that the company was not involved in gambling or related activity in Burma, although they were accused of doing so in Cambodia and the Philippines - but also that they would try their hand at casinos in Burma, since the government had just recently legalized foreign investment in the gambling industry.

For the past five years, every piece of western journalism that has covered the scam cities takes these statements at face value. The coverage has been especially lacking in depth and critical approach in the past six months since the scam compound issue has really heated up and culminated in US sanctions and a Burmese military raid on Shwe Kokko.

The question that nags me is - why is a single statement from an insignificant diplomatic outpost taken as gospel truth?

This is one part of a broader problem in approaching organized and state-sanctioned crime in Asia - taking statements at face value, even when the actions of those involved say otherwise.

The other major issues in understanding this topic are that the western press doesn’t have the right narrative framework to talk about the issues, and they almost exclusively rely on other anglophone research, press, and information when writing their stories.

It’s time to tackle all of these problems head on.

If the Chinese embassy in Burma denied that the Shwe Kokko compounds were part of the Belt and Road, what evidence can we find that proves otherwise?

Who really is She Zhijiang, the architect of Shwe Kokko, where billions of dollars were scammed from Americans? Who supported him and when? What was the relationship he had with the Chinese government, and more importantly, the business and social guilds in that country?

She Zhijiang, The Scam Man

She Zhijiang had a great year in 2017.

Not only did his company, the Yatai Group, break ground on what would become a multi-billion dollar illicit gambling and fraud operation - stealing the hard earned dollars tens of thousands of people from around the world - but he would also be elected as the Executive Vice President of the China Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs Association.

The serving President of the organization at the time, Xu Rongmao - an Australian based real estate developer of Shenzhen properties - anointed She Zhijiang with the title, along with eight others at this conference.

The funny thing was that in the eyes of China’s courts, She Zhijiang was a fugitive. Five years prior, in 2012, he was convicted in a separate scheme for defrauding Chinese citizens and running an illegal gambling operation out of the Philippines. But that didn’t stop him from receiving the prestigious title, securing his place in the upper-echelons of the international Chinese business elite.

As 2019 rolled around, She Zhijiang kept busy.

His scam empire in She Kokko was humming. Concrete was being poured, contracts were being signed, and tens of thousands of people - who were coerced into the work with promises of high-paying tech jobs or romantic flings - were being trafficked into compounds housed in that Special Economic Zone.

He also had a lot of hands to shake - and not just in Burma.

He spent 2019 globetrotting from Beijing to Bangkok - as an honored guest of such organizations as the China Center for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE), the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese (ACFROC), and the China Federation of Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs (CFOCE). I know, they love the long acronyms - there’s nothing I can do about it.

On April 16, 2019, She Zhijiang attended an event hosted by the Sichuan Provincial People’s Government in Chengdu, the provincial capital. It was called the “2019 Belt and Road Overseas Chinese Business Summit” and it attracted over 300 participants, including representatives of overseas Chinese businesses from 46 countries and regions along the Belt and Road - from Asia to Africa.

Surely this is a man of upstanding moral character and an honest businessman - the kind that you can look in the eyes, shake hands with, and call a deal a deal and have it be square.

How else could you be invited to such prestigious gatherings like the one in July 2019 at Beijing, where She Zhijiang and the Yatai Group made a deal with the CCIEE, a public policy think tank based in the Chinese capital.

The agreement between the CCIEE and the Yatai Group’s subsidiary in Burma laid out plans for providing “top-level design to the Yatai International Smart Industrial New City (also known as Shwe Kokko), offering intellectual support and guarantees in various aspects such as infrastructure, construction, and engineering .”

Other parts of the press release implicate government groups in China as collaborators in planning, building, and promoting the Yatai Group’s projects in Burma and the city that would house the scam compounds. More importantly, these are identified as Belt and Road projects. This is all in black and white:

Over the past two years, with the support and assistance of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese and the China Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs Association, the project has made rapid progress. Commercial buildings, commercial streets, KTVs, bars, high-end villa complexes, and hotel complexes have been put into operation one after another. All major construction projects are under construction in an orderly manner, and the project has developed rapidly and achieved remarkable results.

Earlier, the China Center for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE), commissioned by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), jointly drafted the “China-Myanmar Economic Corridor” plan with the Myanmar government. This plan serves as a key tool to promote the alignment of development plans between China and Myanmar, open up international transportation corridors between the two countries, expand the affected areas, and broaden the scope of exchange and cooperation. CCIEE has consistently paid close attention to the construction of the Asia-Pacific International Smart Industry New City and actively contributed ideas and suggestions for its rapid development. Currently, private enterprises have become an important force in the Belt and Road Initiative, playing an indispensable role in its construction.

The importance of this meeting should be underlined.

The CCIEE operates under China’s National Development and Reform Commission and emerged as an effort by Chinese policy leaders to “facilitate broad domestic and international policy discussion,” which brought together politicians, business leaders, and academics. The think tank has a tight relationship with the Chinese government and sits a few hundred yards from the Zhongnanhai, which houses offices and residences of CCP officials.

Witnesses at the signing ceremony in Beijing included high-ranking members of the ACFROC, which is a people’s organization of the CCP and holds 27 seats in the country’s national committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. It’s an organization with an explicit goal of influencing overseas Chinese through various cultural and business institutions.

Also in attendance was one Mr. An Chen, vice president and secretary general of the China Federation of Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs.

A month before the conference in Beijing, She Zhijiang had another gathering to attend in Bangkok.

The guest list included 130 people with dignified attendees such as a ranking member of the Thai royal family; General Chusin Anprasit, director of the Central Election Commission of Thailand; Li Zhuobin, vice chairman of the ACFROC; and Mr. An Chen, vice president and secretary general of the CFOCE - the same Mr. Chen who was at Beijing.

Presidents and chairmen of other business organizations, like the Beijing Chamber of Commerce in Thailand, showed up alongside leaders and social elites from Burma and China.

One interesting name made the guest list - one Wu Nanjiang (吴南江), president of the Hongmen Chamber of Commerce of Thailand.

Mr. Nanjiang can be seen wearing the bright yellow tangzhuang, standing on the left. I’ll get more into the Hongmen, or the Vast Family, a little bit later in this essay - but I want to point out that they are found at every scam compound providing security on the ground, ensuring that the money keeps flowing without a hitch.

It’s a dirty sort of job, with coercion and muscle needed to keep things running smooth. Most of the grunts - who are called “piglets” (猪仔) in Chinese - doing the scamming were tricked into coming under the pretense of high-paying jobs, with their passports stolen, and the threat of beatings if they don’t hit their weekly scam quotas. The Hongmen goons on the ground make sure they don’t leave.

After the signing ceremony, a dinner was held. She Zhijiang delivered a toast and expressed his gratitude on behalf of the Yatai Group, which was at that very moment laying concrete for scam compounds - with many that were known and active. He thanked everybody for coming and for their friendship, which would lead to a new phase of the China-Thailand-Burma Economic Corridor.

Another sure sign of one of Belt and Roads main five pillars, cultural exchange.

She Zhijiang could cheers to that.

There might remain a corner of doubt in your mind, “What if they didn’t know? She Zhijiang was selling a dream, these civic and business leaders were just duped by a conman.”

It’s a fair assumption - and it’s more or less the line that western journalists have tossed out as truth in their rags.

The problem with the assumption is that She Zhijiang was a known fugitive and scammer since 2012 - a fact I brought up before. It wasn’t any big secret. He was wanted by courts in China for illegal gambling operations he ran in the Philippines, and he even went to Cambodia to acquire citizenship and a new passport so that he could continue to travel freely.

The odd thing about that is that as a supposed fugitive, with a rap sheet to match, She Zhijiang was courted by the organizations that represent Chinese political, social, and business interests in China and around the world.

He was even elected as an Executive Vice President of the China Federation of Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs. She Zhijiang wasn’t an outsider, even as a fugitive. His meetings with these state-sponsored international guilds, business groups, and trade organizations was due to him literally being appointed as one of their top-ranked members.

This position gave She Zhijiang direct access to a network in China and other countries, too - Burma, Thailand, Hong Kong, Italy, New Zealand, and Australia.

That’s right - these groups aren’t just in Asia.

Italy and the land down under. How were these countries involved?

An International Body Emerges

Days after She Zhijiang was in Beijing meeting with the CFOCE, a meeting took place in Milan, Italy.

A delegation from Zhejiang (not to be confused with Zhijiang; Zhejiang is a Chinese province), led by one Xiong Jianping, former Vice Governor of the province and member of the Standing Committee of the Zhejiang Provincial Party Committee.

A dyed in the wool, honest to goodness member of the CCP. Here’s his Wikipedia article in Chinese.

Mr. Jianping gave a speech that encouraged overseas Chinese to “leverage their strengths, actively participate in the Belt and Road Initiative, and contribute more to promoting friendly exchanges and cooperation between China and Italy.”

He went on to say that, “Zhejiang-born Chinese living in Italy have established a solid economic and industrial foundation, personal connections, and business channels. Overseas Chinese have multiple advantages, such as familiarity with local laws and a fusion of local and regional cultures, which will surely be fully demonstrated and utilized in participating in the Belt and Road Initiative.”

This demonstrates an understanding of the five pillars, especially trade facilitation and cultural exchange, identified in the speech by President Xi that kicked off the Belt and Road back in Kazakhstan in 2013.

She Zhijiang wasn’t at this meeting in Milan, as he was likely in Beijing, but a front page article in the overseas edition of the Chinese Communist Party’s state newspaper People’s Daily includes both She Zhijiang’s meeting in Beijing, right alongside the event in Milan.

This is akin to an official press release from the White House putting a positive spin to a meeting of Bernie Madoff and his ponzi-scheme victims in Hollywood, next to an article of a boring trade deal about selling soybeans to Botswana. If that picture confused you, read it again until it makes sense.

In September 2017, as the Yatai Group and She Zhijiang were building the foundations of what would become Shwe Kokko’s scam compounds, the 14th World Chinese Entrepreneurs Convention was held in Burma’s most populous city and former capital, Yangon.

A reported number of 2,000 of “elite Chinese entrepreneurs from around the world” attended the gathering. The event’s theme was “Establishing a Historical Milestone through Burma’s Economic Reform.” And the focus was on the Belt and Road Initiative, how working with new ideas and cultural exchange could encourage development by international Chinese business interests.

I’m fairly certain that She Zhijiang was in attendance. I found the photo above, which I believe was taken at the event, but I’m not conclusively sure - as it could’ve been another meeting he had with Colonel Saw Chit Thu, who I discussed in a previous section.

But what I do know for sure is that a delegation from the Chinese Chamber of Commerce of South Australia showed up.

Here are some photos of who was there. A red carpet event! Fancy.

Send my regards to the chef.

And this photo under cozy lighting.

Maybe some of my readers can identify these attendees - I have found a few of their names, but I’ll wait to see if they want to contact me to correct the record before I let that information out.

I bring in this group from Australia - who I’m not implicating in the building of Shwe Kokko, just to be clear - because in 2017 that country was the home to Xu Rongmao, who I mentioned in the previous section, the then President of the China Federation of Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs. The same exact organization that lifted up She Zhijiang, a known scammer and fugitive at the time, as an Executive Vice President.

Xu Rongmao is no small fry.

He’s one of Australia’s wealthiest people, consistently making the top 40 list of billionaires in the country, and in 2017 he was ranked 8th in the country. He built his fortune in real estate through his company the Shimao Group, and is reportedly one of the top developers in the cosmopolitan megacity Shanghai.

He also happened to be at that September 2017 World Chinese Entrepreneurs Convention in Yangon, Burma - where Belt and Road for the country was the main theme.

It gets better still.

Xu Rongmao, a Chinese billionaire living in Australia, president of the CFOCE - gave a speech that officially launched the Yatai Water Valley Economic Zone investment project on September 16th.

This exact project is what would become, under a different name, the Shwe Kokko Special Economic Zone, and it is what the Yatai Group was instrumental in building (Note: Yatai will translate as Asia Pacific when brought to English; that is to say, the company and this Special Economic Zone share the common Chinese word Yatai 亚太).

Mr. Rongmao went on to say in his speech that, “The Shuigou Valley (Chinese pronunciation of Shwe Kokko) investment project is not only a model of in-depth economic, trade and cultural cooperation between Myanmar and China, but also an important achievement of this World Chinese Entrepreneurs Convention. It is also the best interpretation of the theme of this World Chinese Entrepreneurs Convention, ‘Burma’s great economic opening, creating a new era in history.’”

This press release goes on to say that the Yatai Group began investing in the Yatai Water Valley Special Economic Zone in January 2017.

The paper also identified the project as being part of a “key economic corridor within the Belt and Road Initiative” and an intersection of the Thai-Burma tract of the Pan-Asia Railway (you can read more about this here, and I did mention it in my article about the occult trade in Singapore here.

I want to underline the weight of what I have just written. I’ll break the fourth wall for a moment - writing conventions be damned, this is that important - and ask you to pause, go back and re-read the five paragraphs above.

If you’ve done that and you’re with me again, I’ll recap: a Chinese billionaire, with Australian citizenship, and who was the president of the same business group of overseas Chinese that She Zhijiang also served as an executive vice president - this man, Xu Rongmao, is the one who kicked off the Shwe Kokko project, the one that the US Department of the Treasury stated in September 2025 scammed “More than $10 billion from Americans in 2024 alone.”

The icing on the cake?

At the opening ceremony of this convention in Yangon, Xu Yousheng, Deputy Director of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of the State Council - a mouthful, I know, but this is an organ of the CCP - read a congratulatory letter from Yu Zhengsheng, Member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

This CCP organization even published news of the convention in Burma on their website.

This is a direct endorsement of the convention from the CCP and not just from low-level, second-rate bureaucrats. These are members of China’s political apparatus who have pull.

On the Burmese side, U Myint Swe, First Vice President of the country at the time, and Acting President of Burma from 2021 until his death in August of this year, said that the convention would “not only promote the friendly development between Burma and China, but also provide opportunities for overseas Chinese entrepreneurs to expand their investment in the country.”

All of this is on the record. It’s not my speculation.

The skeptical among you, those who are looking for any excuse to wiggle out from the metric tons of evidence I’m laying out on this page, will play this card - “These officials couldn’t have known what was going to happen in Shwe Kokko. The scams hadn’t happened yet in 2017.”

And maybe that single wild card does beat my royal flush. Somehow, I doubt it though. Something in my gut, above and beyond everything that I’ve written, tells me that everybody who endorsed the Yatai Group and what was becoming the Shwe Kokko Special Economic Zone knew exactly what was going on there.

How could they not? It wasn’t a secret that She Zhijiang had an extensive criminal background, as he was involved in illegal gambling operations in the Philippines and had taken up Cambodian citizenship, where he also ran online casinos that defrauded Chinese citizens.

Now, everything that I’ve submitted for your consideration so far has been rock-solid, so perhaps you’ll permit me to indulge in some speculation for a moment.

On the Chinese language Wikipedia page for She Zhijiang, there’s a link to a November 2018 state visit that President Xi made to Manila, Philippines.

It’s rumored that She Zhijiang was in attendance. I haven’t found other sources to corroborate this information, but I’m sure they’re out there in the sea of Chinese language social media - an eldritch depth that I do swim in, but is much too vast for me to find everything.

Then there’s this post on X, made on January 11th, 2025, that claims the fraud cities in Burma can be connected to Geng Zhiyuan, son of the former Vice Premier of China Geng Biao. The post goes on to explain that Xi Jinping served Geng Biao as his secretary, and that his son Geng Zhiyuan did the bidding for President Xi in Burma.

There are some interesting details to consider here. In 2015, Geng Zhiyuan became president of the China-Burma Friendship Association, an appointment given by President Xi himself. If we put this on the timeline of everything that I’ve laid out above, it would stand to reason that Geng Zhiyuan had a role in, approved, or at least was aware of and looked the other way from the criminality that was brewing in Burma by international Chinese actors.

The post goes on to claim that Geng Zhiyuan had three primary tasks: connect with anti-governmental forces, which we know happened as a matter of Chinese state policy, as they courted ethnic rebel groups; manage and control Burma’s underworld organizations, which we have demonstrated with the tacit connections between She Zhijiang and CCP organizations; and lastly, to bribe and recruit officials at all levels of Burma’s anti-democratic government.

Here’s a photo of Geng Zhiyuan on the back row left, Xi Jinping on the right, with an elderly Geng Biao in the center.

I don’t want to muddy the waters here, as my argument is as pristine as an Icelandic glacier, but I do want to give you a peek inside the conspiratorial, rabble-rouser corner of Chinese language social media when it comes to these matters.

Besides, these vantablack depths of the Chinese web sometimes produce gems.

Little glistening nuggets that can paint a picture worth 10,000 words.

Where the Triads Go: Shwe Kokko, KK Park, Shuigou Valley, and Other Scam Cities

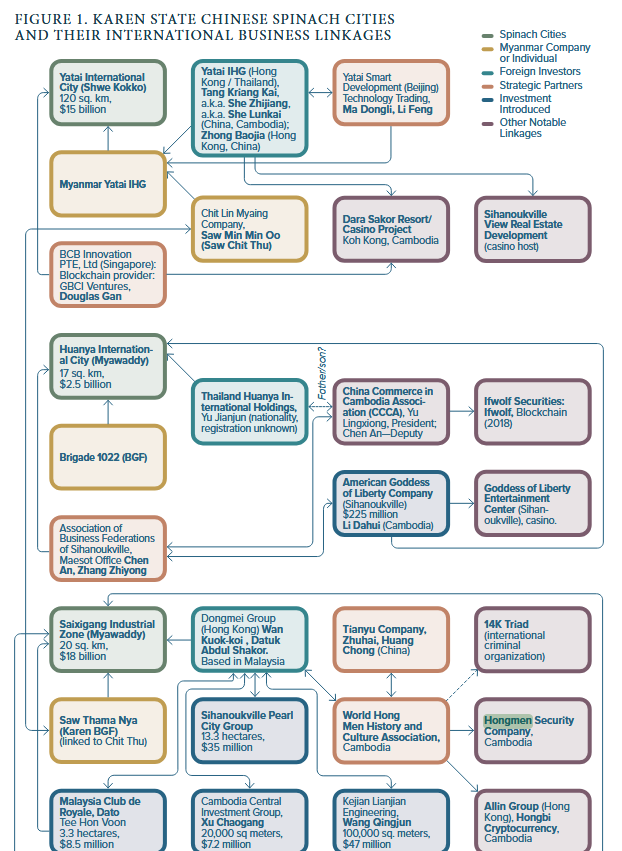

In that same thread on X, another user posted a reply with this image attached.

After a bit of sleuthing, I found the source of the infographic - it was first published by the news outlet HK01 out of Hong Kong.

I recognized some of the faces, places, and names, but I knew there was more to the region than I had found by looking solely at She Zhijiang and the Yatai Group.

Let’s break down this infographic.

The header’s top two lines say:

詐騙園區死灰復燃

泰緬邊境群狼割據地圖

Scam compounds have been resurrected

Map of warlords dividing territories along the Thailand - Burma border

The first pair of faces we see are people who we’ve already covered, Colonel Saw Chit Thu and She Zhijiang, who partnered together to build Shwe Kokko. But there are other scam compounds in the Shuigo Valley under their direction and protection, too - Apollo Park (阿波罗园区) and Yulong Bay (御龙湾).

These two companies are respectively ran by the Apollo International Investment Company Limited and the Yulong Bay Resort Tourism Development Company Limited, and were built between 2019 and 2021. Shareholders in these companies again include the ethnic Karen rebel military faction along with Chinese citizens.

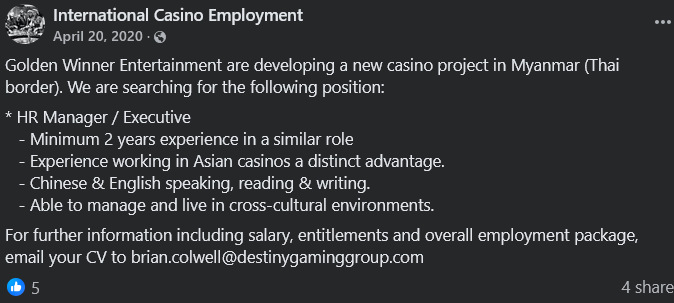

One of the casinos that operated there, called Golden Winner, was set up and ran by an Australian citizen by the name of Brian Colwell.

The operation was registered as a business in Hong Kong under the name of Destiny Global Group (DGG Asia Limited), which Colwell described as “Asia’s most comprehensive gaming management group.” He served as the company’s COO from December 2018 to December 2020, then again in the middle of 2022 through 2023.

Colwell described the Golden Winner casino as operating under the Yatai Group development project, which dealt mainly in cash.

He posted job ads during the COVID pandemic, as people struggled to find work in the region, writing on his LinkedIn that “While most casinos are downgrading their staff, we are increasing due to expansion.”

How many of those people ended up getting roped into the scam compounds is hard to say, but the questions can be raised - what did Colwell know about She Zhijiang, the scam compounds, and the clients that lived it up and gambled in his casinos?

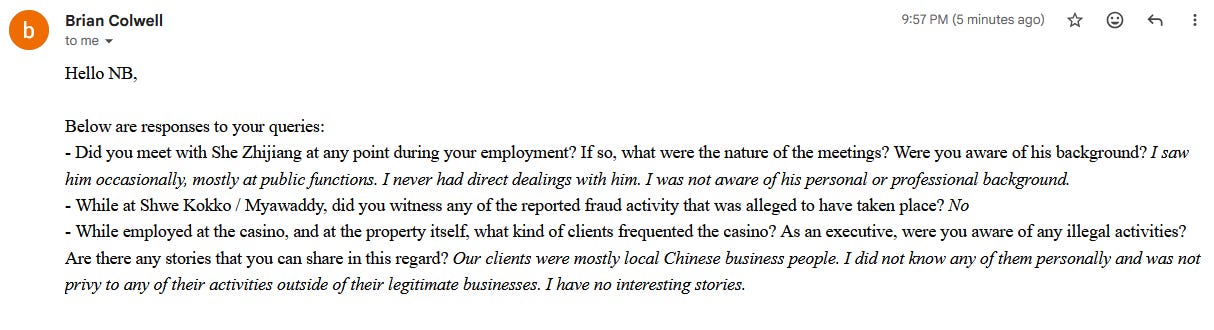

I’ve posed the same to Colwell by email and he responded with the following:

When he responded to other news outlets, he denied any knowledge of what was happening in Shwe Kokko - and claimed that he was operating an above-board live casino.

He denied it when I asked him, and he was quick with his responses, so I will take him at his word.

But at the very least, citizens of western countries should be pressed about their involvement with places like Shwe Kokko, as it’s much more difficult to reach the criminal Chinese players behind these operations. This is why I reached out to Brian, since his name has been included in several articles related to this issue - and I believe he has cleared his name.

Can the same be said of the others?

Back to the infographic that we opened this section of the essay with:

Below the first pair of faces, are another three.

Saw Moe Tone, another high-up brass in the Karen ethnic armed rebel group.

Xiong Shija (熊世佳), who is reportedly the boss of the Jinxin Park, another scam compound, and who also maintains a close working relationship with Colonel Saw Chit Thu.

And the third person, Ji Xiaobo (紀曉波), a Chinese national, son of billionaire businesswoman Cui Lijie, and a business executive who has ran casinos in Macau for over 15 years. He has a child with the famous Taiwanese actress Pace Wu and is currently wanted by both the FBI and the Beijing courts. According to reports, he’s fled to Japan to avoid trial.

Finally, the last images describe KK Park, which has probably received the most press in regards to scam compounds in Burma but is by no means the largest or most significant, along with other facilities with the names of Rego High-Tech Town (雷格高新鎮), and the Dongmeisai Xigang Industrial Zone (東美賽西港產業園區), which was built by Wan Kuok Koi - a high-ranking member of the 14K Triads.

Many of the Chinese who are involved in criminality in Southeast Asia - the narcotics trade and those behind the development of the scam cities in Burma and Cambodia - are known members of various Triad groups.

Wan Kuok Koi (or “Broken-tooth”), the former leader of the Macau branch of the 14K triads and a major player in both the drug trafficking and fraud world, was instrumental in setting up the Dongmei scam compound and also provided security to similar scam compounds and Belt and Road projects throughout Asia by way of his Hongmen Triad company.

Private security teams dominate the scene on the ground in Cambodia and Burma. A detailed report from the Washington-based Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS) in 2021 noted that many of those providing security through the Hongmen weren’t gangsters, but rather former members of China’s security forces. They can earn top dollar in the risky zones and projects along the Belt and Road in far-flung places like Burma, Cambodia, Central Asia, and Africa.

“Private security companies can defend Chinese economic interests while allowing China to avoid the material and reputational risks that arise from putting boots on the ground,” the report said. “These private security companies can also serve as conduits of Chinese soft power. The industry also provides cover for people with ties to organized crime, like Wan, to run armed companies in a host country.”

The US Department of the Treasury levied sanctions against Wan Kuok Koi in 2020. In the press release, it details how he founded the Hongmen History and Culture Association in Cambodia in 2018, which was a way for the Triads to legitimize themselves by providing private contract security to businesses involved in the Belt and Road Initiative.

The Hongmen association recruited elites in Malaysia, Cambodia, Thailand, Burma, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, China, and even Europe and the Americas - according to its website, the association established 12 international branches with its headquarters Macau.

The Hongmen’s stated goals are to “promote the history and culture of the Hung Society, inherit its spirit of loyalty and righteousness, unite the strength of Chinese people around the world, love the country and its people, and make every effort to contribute to the development and construction of the nation and the peaceful reunification of the two sides of the Taiwan Strait.” Here’s a link to their original website.

The concept of jianghu (江湖) is also promoted by the Hongmen, which is an ancient ideal of brotherhood, that is tied to the underworld and rebellious figures throughout Chinese history, but also has idealistic associations with martial arts and mythic heroes.

Its business interests involved real estate, the security operations at scam compounds, along with launching crypto currencies.

In July 2018, it was reported that Wan Kuok Koi launched an ICO in the crypto space, which netted the gangster over $750 million in 5 minutes. As with his other operations, the company behind the project was based in Beijing, but Wan Kuok Koi toured Southeast Asia - from the Philippines to Malaysia - promoting the launch.

Wan Kuok Koi recruited top talent and the well-connected from all across Asia, including diplomats and former ranking politicians in Malaysia, to lead the operations at the Dongmei scam compound in Burma. Some of these individuals include Datuk Abdul Shakor bin Abu Bakar, a former Malaysian diplomat who worked in Egypt; and his wife, Dr Mashitah Ibrahim, who was a former Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department in Malaysia.

Here’s one of those Charlie Conspiracy charts, this one produced by the United States Institute of Peace, a non-profit established by Congress, with board members that include Pete Hegseth and Marco Rubio.

Take it for what it is, as it could be read as NGO-coded, but the chart is accurate enough and is a decent visualization of what this essay has shown so far. There are also a lot of great source material and references in their report.

It should be noted that Wan Kuok Kai is a known associate of Tse Chi Lop, a founding member of the Sam Gor crime syndicate, who were likely involved with the large narcotics bust that I opened this essay with - and controlled upwards of 70% of Asia’s entire drug trade. Hundreds of billions of dollars in narcotics production and smuggling.

As you see, everything comes full circle.

The drugs, the scams, the Belt and Road, public-private partnerships, the five pillars laid out by President Xi - it’s all part of a process, that is for China to spread its influence out into the world, especially its developing corners.

I want to take a big step back here. While doing research for this essay, the amount of information, the people involved, the shell companies, the meetings, conferences, and conventions, the ties to high-level military, business, and political leaders in Burma, Cambodia, Thailand, Hong Kong, and China, all becomes overwhelming.

I’m only sharing a fraction of what I’ve uncovered - you should see the stacks of other notes I took for this essay - and have laid it out in a way that might be able to form a coherent narrative.

Ultimately, there are hundreds more high-level players involved with these scam compounds, which are defrauding Americans as we speak.

The current tactic to combat this problem, at least from the US government, is to play whack-a-mole by leveling sanctions against some of these top targets - like She Zhijiang and Wan Kok Koi - but when one of them falls, another takes his place.

Now that the scope of the problem has been established - and I’ve done my job at flinging dozens of acronyms and Chinese names at you - maybe it’s time that we zoom in on the operations of these compounds, get a little slice of life, and feel what it’s like to be on the ground as Americans are scammed of their hard-earned dough.

The Mechanics of the Scam

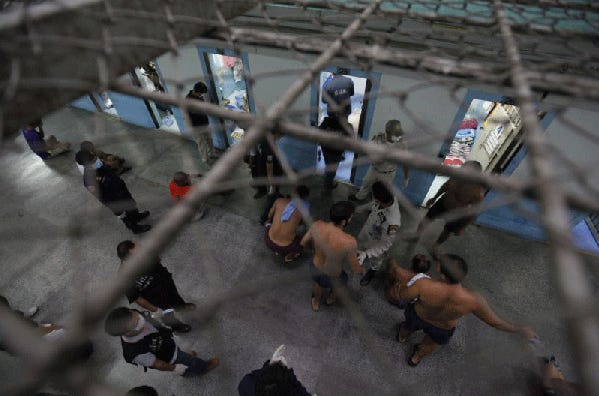

As night falls on the Moei River, Shwe Kokko and its scam compounds remain brightly lit, a dazzling spectacle of neon lights that stretch on for miles. A buzzing nightlife of karaoke joints, clubs, and casinos keep the big shots behind the fraud industry entertained, while the “piglets” pull night shifts inside the concrete labyrinths - with their targets just waking up in America and grabbing lunch in Europe.

Now that we’ve firmly established the people and groups behind the scam cities - they they weren’t just a ragtag bunch of low-level gangsters, but rather a network of connected Chinese billionaires, trade organizations, and likely members of the CCP itself - and that there are many of these scam cities operating in Southeast Asia, disappearing and popping up again as the winds of the law sweep them up and drop them on new ground again, let’s look at how these operations work.

The primary swindle that is used to target Americans and others in the west is known as the “pig butchering” scam. Its concept is simple and effective.

The scammer will connect with the mark through a social media site, or even more effectively a dating app. The conversation moves to Whatsapp or WeChat where the scammer builds rapport with the mark over the next days and weeks.

Nearly in all cases, the scammer will appear to be a younger, attractive woman - typically Asian, a jet-setter type, well-heeled, fashionable and sporting designer handbags, jewelry, and trips to exotic locales. The scammer will tell the mark that they will be visiting the US, Canada, the UK, Australia - or wherever else the mark may be living - in the next few weeks. Older, lonely people are the easiest targets.

Conversation inevitably turns to how each person makes their living, and the scammer will introduce the idea of crypto trading - along with mentioning how successful they’ve been at it, which funds their lavish lifestyle. The seed is planted and shortly after the scammer will ask the mark if they want a part of the action. In most cases, the mark is unaware and unfamiliar with how cryptocurrency works, but they may have read an article on bitcoin or seen it on the news.

The scammer will offer to train the mark in the trading opportunity. All the mark has to do is “follow” the trades of the scammer and they will profit handsomely. Once the mark agrees to the proposal, they’re asked to convert money to cryptocurrency - like USDT or bitcoin - and a fraudulent trading platform is sent to the mark so they can transfer their funds to it.

Usually, a bit of doubt will remain in the back of the mind of the mark. Psychological trust hasn’t been firmly established, but they’re willing to take a small risk, so an equally small deposit will happen - say $500 or $1,000, something that would sting a little but nothing life ruining.

The “fattening of the pig” step of the swindle happens next. The mark follows a trade, profits, and is able to withdraw the sum. Everything happens without a hitch, and it’s this element that resolves any lingering doubt in their mind. Now that the mark is primed for a bigger score, the scammer will suggest to put in a much larger sum. Ten thousand, twenty thousand, even hundreds of thousands of dollars have been reported.

Alongside this, the scammer will escalate the potential romance - and right after they’ll withdraw the affection they offered in the past weeks. Younger women who have been recruited by the scam compounds will step in at this point to do video calls with the mark, to prove who they are. Most communication other than that will be by text, so it’s usually men sitting in the compounds of Shwe Kokko who are posing as the jet-setting beauties.

The mark will mix up the emotions of money and love in their mind and believe that in order to get the affections back of the person they thought was a legitimate romantic prospect, they’ll go ahead with the deposit of the larger sum into the fraudulent trading platform.

After that deposit is made, the work is done. Within minutes of the large crypto transfer, the fraudulent trading platform website is taken offline and all communication channels between the scammer and mark are cut off and blocked.

The psychological wallop that the mark feels after the swindle will produce a great deal of shame, regret, and embarrassment. Normally, they will keep their losses to themselves - not telling family, friends, and most importantly law enforcement. Even if they do go to the law, there’s not much that can be done.

The crypto transactions to international entities can’t be reversed. And most of the time, the mark still thinks they were dealing with a young woman who pulled off the scam. They’re not even aware of where they actually are, being under the assumption the scamming woman was from Hong Kong or Singapore, not knowing it was an operation being conducted out of a compound in Burma or Cambodia. Detectives file the case, report it to federal authorities, and say they’ll update the mark if anything can be done.

This story has repeated itself tens of thousands of times over the past ten years, and has escalated to the point where in 2024, the US Treasury Department reported that over $10 billion was scammed from Americans at one compound alone - the one in Shwe Kokko.

Life in Shwe Kokko might seem halfway normal. The Yatai Group even established a library there - and one wonders what volumes those shelves hold. Are they books of the trade, to educate the scammers in the refinements of their crimes? Or are they books of philosophy, nihilism, antinomian tracts...

In March 2023, civic leaders from China, Burma, and Thailand met to discuss the scam compounds as the issue could no longer be swept under the rug and ignored. They agreed that shutting off power and telecommunications to the industrial parks would be an effective strategy to curb the crime. This is a tactic used in Yunnan, China to fight the scam centers that pop up there.

Of course, the scammers adapted. The casino operators and fraud centers brought in diesel-fueled generators to keep the show running. This cut in to profits as operating expenses rose, but that just meant that the “piglets” behind the screens had to work longer hours and produce more under threat of beatings if they didn’t hit their financial targets.

As for communications, over 2,500 Starlink routers were brought in to keep Shwe Kokko and the other scam cities in touch with the world. Each router can connect up to 300 devices, so you can do the math in terms of the scope of the problem. As of October 22nd, 2025, SpaceX has reportedly cut off service to Burma completely in response to the issue.

The question must be raised - who are these “piglets” on the ground, the ones behind the screens doing the dirty grunt work in these scams? The whole thing is a numbers game, after all, like any business venture. Tens of millions of messages must be sent before one pays off big. Why would anybody sign up for this sort of job?

It’s a fair question. Here is a Facebook page branded under the Yatai Group, which includes posts that encouraged job seekers to come to Shwe Kokko for the free food, easy office life, and fine accommodations. Here are some of the photos from early 2018.

Hard at work scamming - true generational talent here.

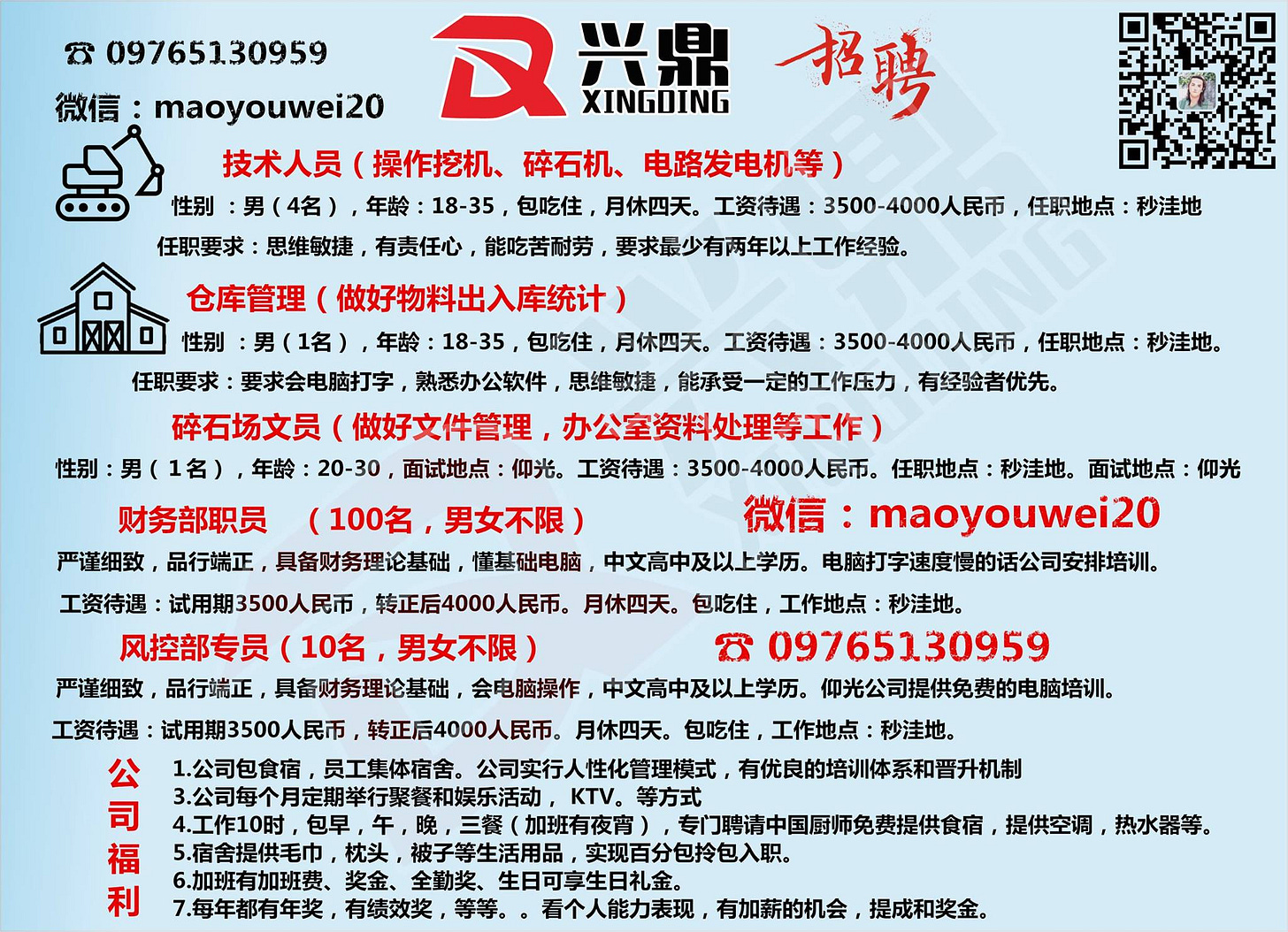

Here’s a job post that advertises a variety of positions, including Finance Department Staff with a starting salary of 3,500 Chinese Remnibi or about $500 USD. Meals and lodging included, 4 days off per month.

Some villas, work facilities, and living quarters of the piglets who would be soon corralled into the scam compounds.

Some of that delicious free food at the canteen! Serve yourself, of course - have to keep costs down.

An inside look at the piglet living quarters. A comfy place to rest a tired head, to prepare for another day of scamming Americans.

The media has painted a picture of the “piglets” being victims of the larger operation. Duped into coming to Burma by way of Thailand, offered high-paying work or their own chance at romance.

Job offers like the ones above are posted across the developing world - Uzbekistan, India, the Philippines, Malaysia, China - that promise easy work with a fat salary at a Thai company - mentionting nothing about Burma or scam compounds.

This part is important, as they typically know nothing about Thailand, and even less about Burma. The offer includes room and board, and once a dubious contract is signed, a plane ticket brings the soon-to-be scammer to the Bangkok airport. A driver will meet them there, holding a sign with the piglet’s name, and is meant to take them to the company in Thailand.

But the driver gets lost, assuring the passenger that they’ll arrive soon enough to the Thai headquarters. Instead, the driver has taken them to the border of Thailand and Burma, drives through an unauthorized crossing, and the prospective scammer is born as a piglet. They’re greeted by Chinese gangsters, members of the Hongmen Triads, who threaten the piglet before taking their passport and phone, then assign him to a station at a scam compound.

This is the narrative, but it’s not exactly true. That is to say, this does happen - and there are plenty of news reports in the western press that detail this exact scenario - but the reality on the ground is much more complicated and disturbing.

When the piglet is trained and assigned to their scam pod - to sit behind one of these screens, like a swine at the trough - a carrot and stick game starts. Beatings are used to destroy their individual will and accustom them to the new work - which is difficult for anybody but a sociopath. Subtle forms of positive brainwashing follow, as some piglets hit big scores and are paid handsomely. These wins are celebrated in the scam compound.

Stories of piglets getting paid massive sums - hundreds of thousands of dollars from a single scam - are circulated on the floor, where computers, cell phones, and tablets buzz with messages sent back and forth between marks and the piglets.

Team leaders and the bigger bosses come to work wearing designer clothes and sporting expensive watches. Aspirational lifestyle flexes.

Commission payouts to the piglets, especially the hefty ones, are turned into the small pleasures that abound in Shwe Kokko and other scam cities. The winners splash cash on take-out food, spend nights at the karaoke joints, take trips to the casinos that dot the area, snort ketamine, and buy sex from the droves of young women that are brought in from Burma, Thailand, Laos, and China for relief. The top performers get to live in comfortable villas alongside the team leaders and other bosses.

The losers, those piglets who can’t hit their quotas, meet a different sort of fate. Some whore themselves out to pay back the money they owe, as their room and board is deducted from a running total against their account. They get by with meager meals, rice and dirty vegetables grown by the local Burmese.

When a piglet lands a whale, celebration follows. According to reports, a million dollar score will bring the big boss to the compound - and the night sky will explode with fireworks over the Moei River, while top-shelf whiskeys spill into the cups of the winners. Those sort of scores aren’t as rare as you’d think, and when they go down, the piglet who closes the book on that swindle will be courted by his higher-ups, brought to the VIP rooms of the scam city’s nightclubs to celebrate - of course, this is done on the piglet’s dime.

Everybody is paid based on performance, that includes team leaders and compound bosses. The average score might net $500 or $1,000, and the team leader’s job is to pump up that number as high as possible. Some reports indicate that if the average swindle isn’t at least $1,500 then the team leader will have their salary withheld.

Failure to hit daily quotas results in cruel and unusual punishments. Every company, scam center, and compound will have their own methods, but here are some that have been reported by escapees.

Forced running under the tropical sun, squatting for an hour with buckets of water balanced on the thighs, an hour of push-ups without rest. If scams weren’t closed after these abuses, then they’ll escalate.

Baseball bats scrawled with a warning “Sold Out” would be used to spank the ass of those piglets who couldn’t seal deals - with some beaten so bad, their cheeks purple and black, that they’d waddle back to their desk unable to sit on their chair.

As the punishments are meted out, piglets could be forced to shout slogans, “I need to change,” “I need to work harder,” “I need to hit my targets.”

At the whim of the boss, an individual piglet may be punished, or the entire team, or even the whole scam compound - even for the failures of one. Stun guns and PVC pipes are reportedly ubiquitous throughout all of the scam compounds, and some of these are attached with notes reading “It’s for your own good.” Those piglets who regularly miss their quotas are called “stun gun eaters” (吃电棍选手).

Hundreds of first-hand accounts of what happens in these scam compounds have made it to the outside. Many more will trickle to the press in the coming months as some of these operations have been raided in Burma and shut down in Cambodia. These recent actions don’t spell the end of this activity, though - as it’s much too profitable to let go.

More importantly, it’s incredibly difficult to retrieve the funds that have been taken, as the transactions are facilitated through a variety of cryptocurrencies and blockchains outside of established, regulated platforms.

As I dug a bit deeper into Shwe Kokko and other compounds, I found some of the crypto companies that were used to bring money into these operations, and likely used to bring money out.

The Crypto Connection

The bitcoin ledger settles billions of dollars in trades per day. Thousands of bitcoin travel from wallet to wallet, pinging across the blockchain, handing off Satoshi’s cryptographic miracle to neophyte and seasoned crypto wizards alike.

On the afternoon of October 14, 2025, the US Department of Justice issued a whopper of a press release. The document lays out a historic seizure of 127,271 Bitcoin, worth approximately $15 billion, from a Cambodian-based business and banking conglomerate called the Prince Holding Group. This monetary seizure dwarfs the previous record, made in June 2025, of $225 million in crypto that had been defrauded through the same pig-butchering schemes.

I’ve often read that the US Federal Government is the largest holder of bitcoin in the world due to these kind of seizures. One wonders that when it’s all said and done, Uncle Sam will own the whole 21 million coins. Forgive me for my speculation.

The chairman and founder of the Prince Holding Group, a Chinese-born man named Chen Zhi, who holds Cambodian citizenship, was named as the prime suspect and indicted for operating the forced labor scam compounds that engaged in pig-butchering scams, just like the ones in Burma. At the time of this article, Chen Zhi has evaded capture.

Kash Patel, the American FBI Director, said about the operation and of Chen Zhi that, “This is an individual who allegedly operated a vast criminal network across multiple continents involving forced labor, money laundering, investment schemes, and stolen assets - targeting millions of innocent victims in the process. Justice will be done and I’m proud of the men and women of the FBI who executed the mission faithfully.”

More than 100 other individuals and business entities have been implicated in this operation. You can find the list here - and scrolling through this list would be fruitful to understand how rampant and widespread this fraud goes.

The assistant director at the FBI’s New York field office stated that, “The scams are rampant, and the FBI is focusing on the biggest cases to try to stop the harm. It’s kind of like jaywalking. You can’t arrest your way out of the problem. But the FBI is focusing on the biggest cases to cut off the head of the snake.”